I’m going to go through all 30 starting rotations, sorted by fewest runs allowed, within the lens of pitch movement synergy. Please read that article first, as these notes assume the reader has the context from that article.

The best team at that in 2022 was the Los Angeles Dodgers. Let’s dive in, beginning with future HOFer, Clayton Kershaw.

Clayton Kershaw

I’ll do a separate piece talking about swing decision value, but essentially, it measures the quality of the swing/take decisions, with positive values better for the hitter and negative values better for the pitcher. For reference, the best hitter by this metric is Juan Soto; the best pitcher by this metric is Kevin Gausman.

Kershaw has beautiful synergy between the fastball and slider, maintaining almost identical vertical movement through the first 0.14 seconds of the ball flight, and near perfect horizontal synergy. More importantly, the pitches have significantly different shapes at the end of their paths. Kershaw is almost a canonical example of the principle of minimizing movement differentials early, while maximizing them late.

Most importantly, as we’ll see contrasted later with Dustin May, Kershaw has incredible late differentiation on the vertical plane, which is ideal for swing and miss stuff.

That brings us to the curveball. Batters are pretty good at picking it up and making above-average decisions on it, which would explain why he doesn’t throw it too much.

My current working theory is that curveballs can generate mediocre to bad swing decisions by having huge break (Adam Wainwright comes to mind), rather than maintaining perfect synergy. That’s not to say that they wouldn’t benefit from movement synergy, but that it can be completely distinct from a movement perspective and still work.

Part of my purpose in going through all 30 teams, is to get a better sense of how synergy and swing decisions work together. I still don’t have a good handle on curveballs.

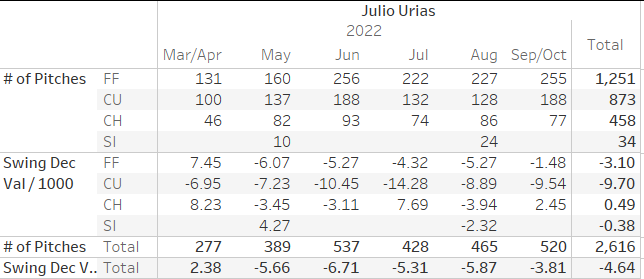

Julio Urías

Let’s begin with the fastball-changeup pair:

Julio gets near perfect synergy vertically for over half the flight of the ball! That’s incredible. The pitches have decent vertical separation by the time they reach the plate, though more drop would probably benefit his swing and miss. Note that the fastball reaches the plate sooner than the changeup, so the vertical differentiation is greater than what is shown here. Horizontally, they pair decently together, which bring us to the curveball-fastball pair:

The curve generates very poor decisions, despite what appears to be very poor synergy on both planes. I need to figure out a way to quantify why certain curveballs generate bad decisions. The framework isn’t perfect, which is part of my motivation to go through every single team.

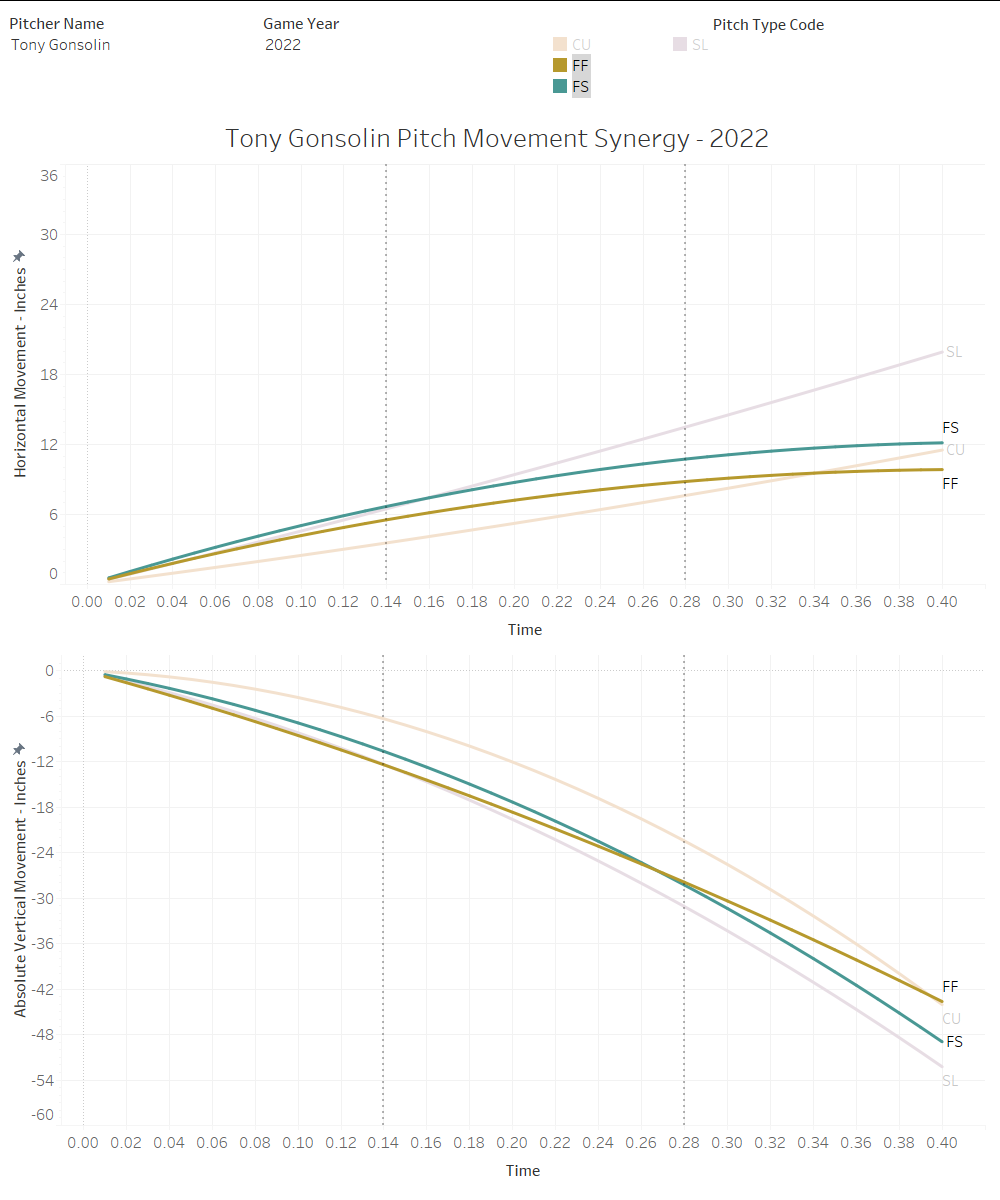

Tony Gonsolin

Gonsolin isn’t quite at the same level as Kershaw and Urías, but as we’ll see there is a very distinct pattern with Dodgers pitchers:

Gonsolin’s fastball and slider synergize extremely well, especially on the vertical plane.

We see a “hump” between the splitter and the fastball on the vertical plane, with the splitter popping up a little, before dropping off. Again, Gonsolin’s best pitch by swing decision value is the curveball, despite it being “easy” to pick up.

One of my working theories is that pure “stuff” and other deceptive qualities factor into swing decisions at least as much as movement synergy (probably more), which makes it hard to quantify the impact. With curveballs that are distinct, dropping in a change of pace 10-20% of the time, appears to be quite effective.

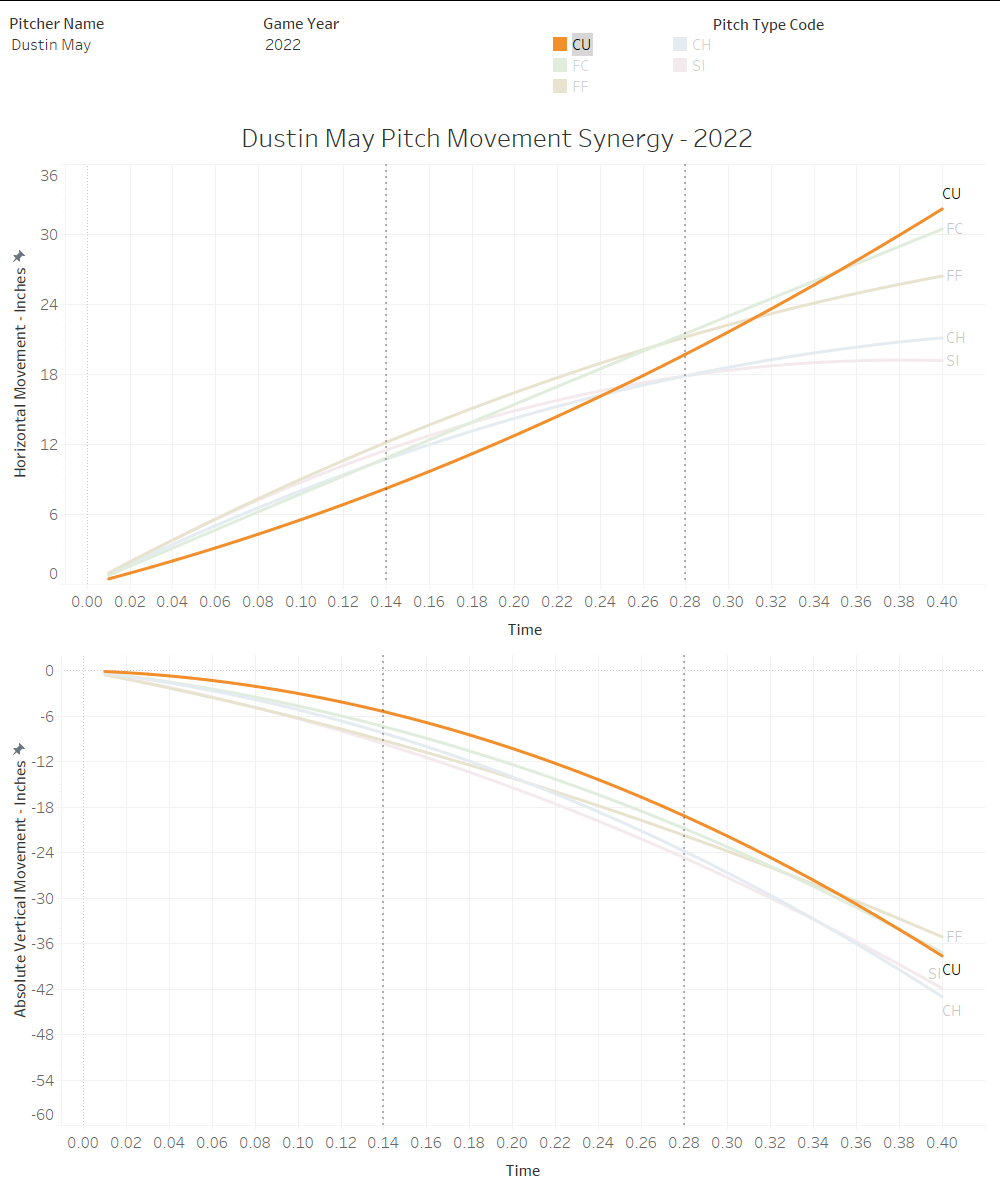

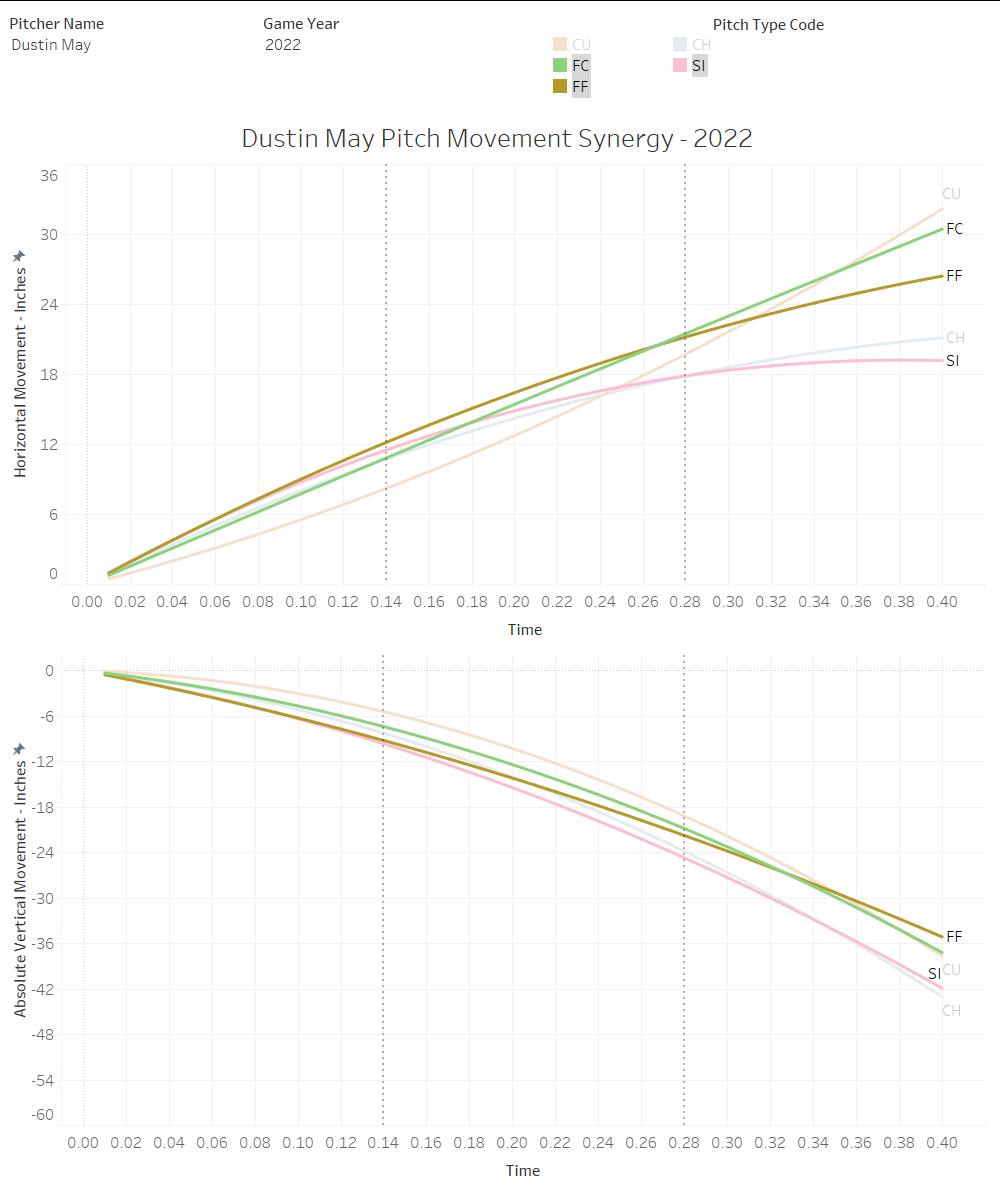

Dustin May

Dustin mixes 4 pitches, which complicates the analysis somewhat. Let’s begin with the fastball-sinker pair:

This pair almost operates like a fastball-slider pair in terms of movement differential late, combined with mirrored movement early.

Much like the prior 3 pitchers, May’s curveball is visually distinct. Unlike the prior 3, he hasn’t generated poor swing decisions with it, albeit in a small sample size.

I have a specific recommendation for Dustin May: He needs more late vertical separation in his pitches. It’s probably the reason he doesn’t get nearly as much swing and miss as you’d expect with his insane stuff. Put another way, late vertical differentiation is more likely to miss the bat than late horizontal separation. I’m sure the Dodgers are aware of this, so if/when they make that tweak, Dustin May may be dusting off batters as he ascends to the upper echelon of pitchers.

For reference, here’s what May looked like in 2020:

If I was a betting person (I’m not, please stop with all the betting ads), I would expect the Dodgers to fix this. I’m all-in on Dustin May.

Thor

Syndergaard generates very poor decisions with his sinker, mostly due to this eye-popping chart:

Syndergaard has 4 pitches that all move the same horizontally for the first 0.14 seconds of the flight and then diverge significantly later. The slider breaks differently than the other 3 pitches on the vertical plane and might partially explain why batters pick it up better.

On the vertical plane, it’s not as great of a story. First, the slider looks like it has a little “bump” early in its flight path, and as with Dustin May, he lacks great vertical separation late. My assumption is that the Dodgers have a plan to optimize his late vertical separation, while maintaining his incredible horizontal synergy. If they can, he’ll be an easy #2/#3 starter again (or better), health permitting. I find it interesting (and providing a sweet sweet confirmation bias high) that the Dodgers targeted a pitcher with great movement synergy.

Concluding Thoughts

The Dodgers know what they are doing with pitchers. One pitcher they let leave in free agency has a movement profile that looks like this (albeit he still generates poor decisions via other methods):

Contrast that to a pitcher they picked up (Syndergaard) and it would appear the Dodgers emphasize movement synergy from both a developmental and acquisition standpoint.

The link between synergy and swing decisions isn’t a lock. There’s so much that goes into pitching, that sometimes synergizing two pitches can be dwarfed by other factors. However, it does, at this juncture of my anlaysis, appear that we can visually see which pitchers struggle to get swing and miss by a lack of vertical separation. I’ll talk more about vertical separation in future pieces, as that is magnified by velocity separation (i.e. the charts are all on the same timeline, but the fastball arrives at the plate sooner).

Next up: The Houston Astros, who don’t care as much about synergy, or do they?